Spaces of Infrastructure: The History and Description of the Manchester Waterworks

A good exemplar of infrastructural geography can be seen in the major Victorian engineering efforts to secure clean drinking water for the people of Manchester. This involved developing a large-scale system of reservoirs along the valley of the Etherow River to gather and store the plentiful rain water falling on the Peak District hills. Known as the Longdendale supply system, it became fully operational in 1877 and was able to deliver over 17 million gallons of clean drinking water per day to the city through a ten mile long aqueduct using only the force of gravity. It was widely celebrated at the time as a truely pioneering piece of engineering and one that brought real public health benefits to the residents of Manchester.

Storing Water Safely

Engineering reservoirs is, at its most fundamental, all about the construction of the core of the dam to hold back the pressure of millions of tons of water. One of the hardest engineering challenges Bateman faced in building the Longdendale reservoir chain was the significant problems he encountered in making the Woodhead dam secure and watertight, in part because of the unstable ground conditions around the chosen embankment site. Some of this detail is captured in this diagram from the book, the 'longitudinal section of puddle trench for the second embankment shewing the geological strata'. (You can examine a high resolution version of this diagram here.)

Bateman recounted the challenge of the Woodhead dam as follows:

"The puddle trench of this embankment was an expensive and troublesome work. The borings, which were taken before the work was commenced, were, as has been stated, very deceptive. They indicated the existence of rock at a depth of about 20 feet below the surface of the ground on the Derbyshire or south side of the valley, and though it was well known that here there was an ancient landslip - the rock which was. supposed to exist was also supposed to be the original ground on which the slip had taken place. Instead, however, of rock being found at this depth large loose stones or blocks of rock were found, sometimes resting on each other; and though the material in which they were imbedded was generally stiff retentive clay, there were beds or "pot-holes" of sand or gravel which it was deemed prudent to follow or cut out. It was, therefore, necessary to go to a much greater depth and distance into the hill than was anticipated." (p.121)

Seeing the Infrastructural System

The History and Description of the Manchester Waterworks runs to 224 pages and has over 50 large and well crafted illustrations including a range of overview maps, detailed engineering schematics, cross sectional diagrams and statistical charts. One of my favourite illustrations is this finely proportioned fold-out map that delineates the sizes and sinuous shapes of the five main reservoirs along the chain, from running in sequence from Bottoms upto Woodhead, plus the smaller reservoirs in side valleys and the various anciliary facilities, connections and conduits.

Following on from the development of the supply system in the Longdendale valley, the growing demand from city and surrounding towns meant Manchester's infrastructural imperatives looked even further north in the 1870s to the abundant water available in the Lake District. Manchester next water supply scheme was to tranform the Thirlmere Lake into a huge storage reservoir and to build a 96 mile long gravity feed aqueduct.

Some further reading:

A good exemplar of infrastructural geography can be seen in the major Victorian engineering efforts to secure clean drinking water for the people of Manchester. This involved developing a large-scale system of reservoirs along the valley of the Etherow River to gather and store the plentiful rain water falling on the Peak District hills. Known as the Longdendale supply system, it became fully operational in 1877 and was able to deliver over 17 million gallons of clean drinking water per day to the city through a ten mile long aqueduct using only the force of gravity. It was widely celebrated at the time as a truely pioneering piece of engineering and one that brought real public health benefits to the residents of Manchester.

The complexity of the waterworks infrastructure is well summarised

in this 1881 diagram. (Image courtesy of Manchester City Archives.)

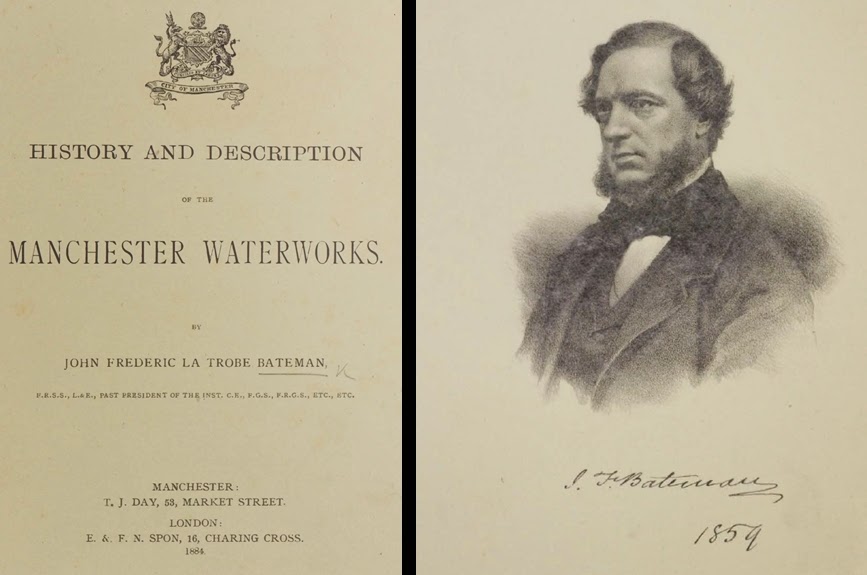

A detailed narration of the Longdendale project, which commenced in 1846 and took several decades to complete, was provided in a book length treatise, the History and Description of the Manchester Waterworks, written by the lead engineer responsible for its design and execution, John Frederick Bateman. His book was published in 1884 and it was a weighty tone packed with factual details and accompanied by over fifty plates.

The whole book, including all the maps and plans has now been digitised through the expertise of the Centre for Heritage Imaging and Collection Care in the University of Manchester Library and is freely available to browse online. (If you want to own a print copy of Bateman's original book, they are available on the secondhand market but they're not cheap to buy.) While the book is somewhat autobiography, and unsurprisingly tends to privilege Bateman's role in the work, it does seem in many respects to be reliable account of the emergence of this infrastructural system.

Browse the full version of the

Storing Water Safely

Engineering reservoirs is, at its most fundamental, all about the construction of the core of the dam to hold back the pressure of millions of tons of water. One of the hardest engineering challenges Bateman faced in building the Longdendale reservoir chain was the significant problems he encountered in making the Woodhead dam secure and watertight, in part because of the unstable ground conditions around the chosen embankment site. Some of this detail is captured in this diagram from the book, the 'longitudinal section of puddle trench for the second embankment shewing the geological strata'. (You can examine a high resolution version of this diagram here.)

"Longitudinal section of puddle trench for the second embankment shewing the geological strata", from the History and Description of the Manchester Waterworks.

Bateman recounted the challenge of the Woodhead dam as follows:

"The puddle trench of this embankment was an expensive and troublesome work. The borings, which were taken before the work was commenced, were, as has been stated, very deceptive. They indicated the existence of rock at a depth of about 20 feet below the surface of the ground on the Derbyshire or south side of the valley, and though it was well known that here there was an ancient landslip - the rock which was. supposed to exist was also supposed to be the original ground on which the slip had taken place. Instead, however, of rock being found at this depth large loose stones or blocks of rock were found, sometimes resting on each other; and though the material in which they were imbedded was generally stiff retentive clay, there were beds or "pot-holes" of sand or gravel which it was deemed prudent to follow or cut out. It was, therefore, necessary to go to a much greater depth and distance into the hill than was anticipated." (p.121)

Seeing the Infrastructural System

The History and Description of the Manchester Waterworks runs to 224 pages and has over 50 large and well crafted illustrations including a range of overview maps, detailed engineering schematics, cross sectional diagrams and statistical charts. One of my favourite illustrations is this finely proportioned fold-out map that delineates the sizes and sinuous shapes of the five main reservoirs along the chain, from running in sequence from Bottoms upto Woodhead, plus the smaller reservoirs in side valleys and the various anciliary facilities, connections and conduits.

"Plan shewing storage reservoirs in the valley of Longdendale", from the History and Description of the Manchester Waterworks

Following on from the development of the supply system in the Longdendale valley, the growing demand from city and surrounding towns meant Manchester's infrastructural imperatives looked even further north in the 1870s to the abundant water available in the Lake District. Manchester next water supply scheme was to tranform the Thirlmere Lake into a huge storage reservoir and to build a 96 mile long gravity feed aqueduct.

Some further reading:

- W. Sherratt, "Water Supply to Large Towns", in the Journal of the Manchester Geographical Society, 1888;

- Tom Quayle's short book Manchester’s Water: The Reservoirs in the Hills (Tempus Publishing, 2006);

- Harriet Ritvo's "Manchester v. Thirlmere and the Construction of the Victorian Environment" in the Victorian Journal, 2008;

- Also a couple of pieces I have co-written:

- Maps, Memories and Manchester: The Cartographic Imagination of the Hidden Networks of the Hydraulic City

- Mapping Manchester and Its Hidden Hydraulic Engineering

Cyber Badger Research Blog

Cyber Badger Research Blog

1 Comments:

You describe these things very impressively.

Post a Comment

<< Home